‘Looking back at my life, I have been lucky to be able to pursue three occupations – medicine, music and archaeology – the last two initially as hobbies, later to become full-time professions.’

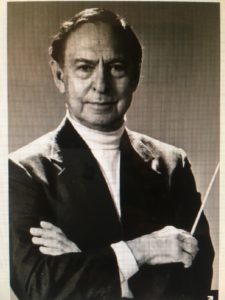

Dr Solomon Bard OBE ED JP

Thus wrote war veteran, Dr Solomon Bard, one of the most remarkable and gifted Jewish ex-servicemen, who left an indelible impression on those around him wherever he went.

He was born in 1916 (before the Russian Revolution) in the small town of Chita in Siberia, one of the most freezing and inhospitable parts of Russia. In 1924 along with other Russians, his parents moved to China where they found a home in Harbin.

While at a Russian school there, Solomon studied music and became so proficient with the flute and violin that at the age of 15, he was invited to play in Harbin’s semi-professional symphony orchestra.

In 1932 the Japanese army entered Harbin and set up the puppet state of Manchukuo and the family moved to Shanghai, where Solomon learnt English and completed his school education. He was then accepted at the University of Hong Kong medical school, from where he graduated with the top award for academic excellence. His parents migrated to South America in 1934.

Dr Solomon Bard (rear left) and Dr Albert Rodrigues (back centre) in Sham Shui Po POW Camp in 1944

In 1939 he enlisted in the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps. This Corps had been established in 1854 as a territorial reserve unit, which in time of war would become part of the regular army. In 1941 he married Sophie Patushinsky, a fellow medical student but shortly afterwards on 8 December 1941, Japan launched its invasion and after a brief period of fierce fighting, Hong Kong surrendered on 25 December 1941. As part of the Field Ambulance, Dr Bard had been exposed to some of the most dangerous areas of the short struggle. He wrote:

‘On the 10th, the Mount Davis Battery, not far from our position, was heavily bombed by Japanese planes, and I was ordered to proceed there for attachment as Battery medical officer.… On the 14th, an armour-piercing shell, possibly fired from a cruiser, penetrated our protected ‘sanctuary’ in the Battery Plotting complex, and fortunately failed to explode, so that some 60 of us sheltering inside escaped from being blown up; we evacuated the complex, since it was no longer safe.’

After the surrender, Dr Bard was taken to Sham Shui Po prisoner of war camp on Kowloon where he remained until his liberation on 15 August 1945. He worked as a doctor in the camp and brought comfort and solace to many of the prisoners by playing the violin and forming a camp orchestra, using makeshift instruments, such as a cello made out of an oil can and combs wrapped in toilet paper.

After liberation Solomon Bard rose to the rank of Colonel in the Corps, which was renamed the Royal Hong Kong Regiment. In 1957 in recognition of his long and meritorious service with the Royal Hong Kong Regiment, Dr Bard was awarded the Efficiency Decoration and promoted to Honorary Colonel of the Regiment for the period 1982-1984.

Meanwhile, after a brief period in England following his liberation and repatriation there, he and his wife returned to Hong Kong in 1947 and he became the head of the medical clinic at the university, serving the needs of staff and students for decades.

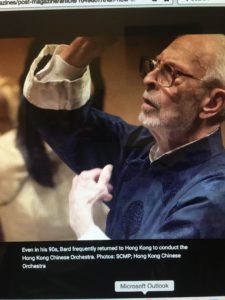

Photo from South China Morning Post

Also in 1947 the Sino-British Club formed the Sino-British orchestra, as part of its efforts to create cultural harmony in Hong Kong, and Dr Bard was appointed its first conductor and conducted its inaugural performance with about 20 musicians. In 1953 he invited a professional conductor to join the orchestra and he remained as its deputy conductor and concert master.

In 1957 the orchestra decided to separate from the Sino –British Club and was renamed the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra. Dr Bard remained in his position with it and it became the first professional orchestra in Hong Kong and went on to attract international musicians and guest conductors. Occasionally he conducted it.

He also added to the number of instruments he could master by learning to play the Chinese flute and from 1983 to 1987, he was the first full time Assistant Music Director of the Hong Kong Chinese orchestra. He participated in this orchestra’s tours of Australia, Korea, Japan and China.

Concurrently with his medical work and his musical activities, during the 1950s he developed an interest in archaeology and local history. He was one of the founding members of the University Archaeological Team, which later became the Hong Kong Archaeological Society and for many years served as its chairman. To further his knowledge in this area, he spent a year in the Anthropology Department of the Australian Museum in Sydney.

In 1976 he became the first executive secretary of the Antiquities and Monuments Office and after he retired from this position in 1983, he participated in a number of important archaeological investigations and produced several important publications such as In Search of the Past: A Guide to the Antiquities of Hong Kong, Study of Military Graves and Monuments: Hong Kong Cemetery, and Garrison Memorials in Hong Kong: Some Graves and Monuments at Happy Valley.

He was Honorary Curator (Archaeology) of the City Museum and Art Gallery and from 1976 for the next 38 years, Dr Bard served as a Museum Expert Advisor on the archaeology, local history and military panels of the Leisure and Cultural Services Department.

In 1993 Dr Bard moved to Australia where he joined NAJEX. On 10 September 1995 an exhibition was opened by NAJEX President, Wesley Browne, at Sydney Jewish Museum entitled Prisoners of War – Pacific Theatre. The exhibition featured NAJEX members, Dr Solomon Bard, Neville Milston and Harry Leslie. He became a volunteer at the Sydney Jewish Museum from 1995 to 2014 and also volunteered at the Australian Museum.

After his death, an admirer wrote publicly:

‘ The museum communities of Hong Kong and Australia have lost a prodigiously talented curator, historian and archaeologist. His legacy will remain in the magnificent body of work he created and in the hearts of thousands of people in the cultural heritage community in Asia. Vale, Solly, may the candle of knowledge you fanned in each of us keep burning.’

In 1994 he was invited to become the first chairman of the Hong Kong Volunteer and Ex-POW Association of NSW, a position he held until 2006, when he was invited to be its patron. Until he was nearly 97, he led their contingent in annual Anzac Day marches.

In 1994 he was invited to become the first chairman of the Hong Kong Volunteer and Ex-POW Association of NSW, a position he held until 2006, when he was invited to be its patron. Until he was nearly 97, he led their contingent in annual Anzac Day marches.

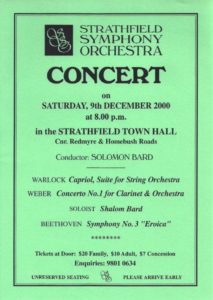

From 1994 to 2004 Dr Bard also conducted the Strathfield Symphony Orchestra, after having been selected by the orchestra from seventeen applicants. His personal charm and generous, unaffected approach was clearly demonstrated in an introduction that he wrote to a history of that Orchestra, as follows:

‘Four years ago I was auditioned by the S.S.O.(no.2) for the post of their conductor. The work we performed was Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7. It is said that experienced conductors know that every orchestra has its own characteristics that distinguish it from others. Half way through the first movement, I realised that here was an orchestra composed of not merely individuals but individualists, each with his or her version of the score! It was a unique experience and the point is, I LIKED IT! Moreover I saw an enquiring expression on nearly every face (when they looked at me), and a feeling of warmth and friendliness, such as I have seldom experienced before, and certainly not in my experience in other orchestras in Sydney. I knew that if I were selected (and I was), we would get on splendidly. The friendly feeling which the Orchestra projects remains one of its blessings (why not advertise it as Strathfield Friendly Symphony Orchestra?).’

‘Four years ago I was auditioned by the S.S.O.(no.2) for the post of their conductor. The work we performed was Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7. It is said that experienced conductors know that every orchestra has its own characteristics that distinguish it from others. Half way through the first movement, I realised that here was an orchestra composed of not merely individuals but individualists, each with his or her version of the score! It was a unique experience and the point is, I LIKED IT! Moreover I saw an enquiring expression on nearly every face (when they looked at me), and a feeling of warmth and friendliness, such as I have seldom experienced before, and certainly not in my experience in other orchestras in Sydney. I knew that if I were selected (and I was), we would get on splendidly. The friendly feeling which the Orchestra projects remains one of its blessings (why not advertise it as Strathfield Friendly Symphony Orchestra?).’

Dr Bard died at Wolper Hospital in 2014 at the age of 98 and after his death several obituaries were published, including in the South China Morning Post, the Sydney Morning Herald, the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong and also by Strathfield Symphony and The Hong Kong Volunteer and Ex-POW Association of NSW.

In his auto-biographical book of essays ‘Light and Shade: Sketches from an Uncommon Life” he tells of his experiences as a doctor, musician and archaeologist – his three great passions in life.

Dr Bard was made an MBE (military) in 1968 and OBE (civilian) in 1976, was appointed a Justice of the Peace in 1975 and in 1976 the University of Hong Kong conferred an Honorary Doctorate on him.

He had two children and five grandchildren.