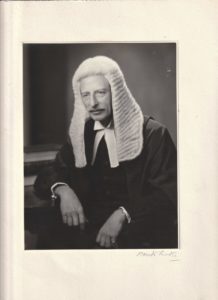

David Mayer Selby

“Lawyer, judge, soldier, university leader, author, public figure, eminent citizen and exemplary patriot. He was also a thorough gentleman; a scholar of great erudition and dignified bearing; a cultured man of broad mind and constant courtesy; a man of courage and compassion; a wise, sound-thinking counsellor.” These were the words of Rabbi Raymond Apple at the funeral service for the former Justice David Selby who died in 2002 at the age of 96.

David Selby, as the oldest of four sons, had been expected to enter his father’s Scientific Instruments business but chose instead to study law following an Arts course. During his time at Sydney University he wrote and acted in University plays, played tennis in the Arts Faculty team, wrote articles for and edited the Law School journal. He also joined the University of Sydney Scouts infantry unit (later the University of Sydney Regiment) and not long after transferred to the First Medium Artillery Brigade.

He was admitted to the New South Wales Bar in 1931 and struggled to build up his practice through the depression years and later. He felt that he had just begun to build a reasonable practice across a variety of jurisdictions when war was declared and he joined up, as did his sister and three brothers.

With an ongoing interest in New Guinea, he volunteered for service there and was sent in 1941 to command ‘L’ Anti-Aircraft Battery in Rabaul, New Britain. In August that year David Selby and his men set sail for New Britain – a militia unit of two officers and 52 men, mostly under 19 years of age, with two old-fashioned 3-inch guns and an obsolete ring-sight telescope. They were to defend Rabaul alongside the men of Lark Force, 2/22nd battalion of the AIF, a small naval presence and No 24 Squadron of the RAAF with four Hudsons and 10 Wirraways as their total protection.

Lieutenant D M Selby and driver Lance Bombardier B R Hartigan in the battery’s Ford utility truck at Malaguna Camp.

On 4 January 1942 the Japanese began their bombardment of Rabaul. As 18 bombers flew overhead, Selby’s gunners fired. They were the first shots to be fired at an enemy by an Australian militia unit and the first shots fired from Australian territory at an invading enemy by Australian troops. The bombardment increased in intensity and within a fortnight, 24 Squadron was virtually destroyed and its three remaining aircraft were withdrawn. On 23 January the invasion began – 5,500 Japanese troops, supported by a strong naval force including the greater part of the Carrier fleet and fifty Zero fighter planes, compared with just over 1,000 fighting men in Lark Force whose commander ordered immediate withdrawal on the basis of “every man for himself” and with no plan for retreat. Chaos ensued and Lark Force disintegrated.

The following day the Japanese, thinking they had silenced all the Australian batteries, performed a victory parade of heavy bombers, dive bombers and fighters. Selby and his men opened fire, shooting down a Japanese bomber, but having comprehensively given away their position, there was no question of remaining there. They destroyed their guns to save them from falling into enemy hands and refusing to surrender to the Japanese, headed for the jungle.

For the next three harrowing months, David Selby led his men through the jungle across mountains and rivers. Ravaged by hunger, malaria, dysentery, tropical ulcers and injuries, many did not survive. Eventually the small number who did survive reached a deserted plantation on the south coast where they remained, looked after by a local missionary for six weeks until a rescue ship arrived and took them to Port Moresby.

Five months in hospital in Townsville followed, during which David Selby wrote the story of the escape, partly to pass the time and partly as a record for his family. It was not intended for publication, but he was eventually persuaded that it was a story that needed to be told and was finally published with the title Hell and High Fever in 1956 with several reprints. Following his release from hospital, Selby enlisted in the AIF and returned to New Guinea where from 1943 to 1945 he was a legal officer with the Australian New Guinea Administration Unit (ANGAU), reaching the rank of Major. At the time of his discharge he was described as a Captain of the Anti Aircraft Battery at Rabaul.

Returning to Australia following the end of the war, Selby attempted to rebuild his legal practice and also served as Chief Legal Officer, Eastern Command, retiring from the Civilian Military Forces with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and with the award of an Efficiency Decoration.

Much of the focus of his post-war practice was in the field of Divorce where he developed a deep sympathy for people whose marriages had broken down. He rewrote the definitive textbook on divorce, served on the Bar Council of New South Wales, lectured for many years at the University Law School, was president of the University of Sydney Law Graduates Association and of the Medico-Legal Association. He was appointed Queen’s Counsel in 1960.

Two years later the Federal Attorney-General asked him to accept an appointment as a Supreme Court judge in New Guinea. Very keen to accept the appointment, he was also conscious of family obligations in Australia and so he compromised by accepting a six-months’ appointment as an Acting Judge in the then Territory. During the appointment he travelled widely to remote parts of New Guinea, New Britain, New Ireland, Manus and Bougainville. He found the experience fascinating and challenging, particularly as he was frustrated by the inappropriateness of having to apply the Queensland criminal code of 1913 which still carried the death penalty to an emerging primitive people who were also bound by their own tribal laws and beliefs. His second book Itambu, describing several of the cases he presided over and with the theme of the onward march of Papua-New Guinea to nationhood, was written during the Law vacation following his return home and published in 1963.

Returning somewhat reluctantly to Australia, it was only six months before he was appointed to the Supreme Court bench and then as Judge in Divorce, where he remained until his retirement in 1975. Much of his long career had been devoted to the reform and simplification of the Matrimonial Causes Act and he was instrumental in the creation of the Family Law Act, which replaced it and introduced a single ground for divorce – irretrievable breakdown of the marriage, in contrast to the original Act which outlined 14 grounds. He wanted to ensure equal rights for both parents, more attention to be paid to the welfare and custody of children and the provision of commonwealth legal aid in certain cases.

Returning somewhat reluctantly to Australia, it was only six months before he was appointed to the Supreme Court bench and then as Judge in Divorce, where he remained until his retirement in 1975. Much of his long career had been devoted to the reform and simplification of the Matrimonial Causes Act and he was instrumental in the creation of the Family Law Act, which replaced it and introduced a single ground for divorce – irretrievable breakdown of the marriage, in contrast to the original Act which outlined 14 grounds. He wanted to ensure equal rights for both parents, more attention to be paid to the welfare and custody of children and the provision of commonwealth legal aid in certain cases.

David Selby had always been interested in Sydney University and in 1964 he was elected as a Fellow of the Senate representing the graduates, a position which he held until 1989. In 1971 he was appointed Deputy Chancellor, continuing until 1986. In May 1991 the University honoured him with the conferring of the rare Honorary Doctorate of the University for his outstanding service and contribution.

In 1975, having reached the statutory age, David Selby retired from the bench. The following year the Premier of New South Wales appointed him State Parliamentary Remunerations Tribunal.

On 26 January 1988 he was made a Member of the Order of Australia for his services to learning, to legal education and to the community.

Throughout his life, both during and after his retirement, David Selby was active in the community. Among other things he served as chairman and later President of the Marriage Guidance Council of NSW (now Relationships Australia); chairman of the Handcrafts Committee of the Australian Red Cross, who awarded him their Distinguished Service Medal and made him an Honorary Life Member; member of the Medical Ethics Review Committee and President of the Arts Graduates Association of the University of Sydney; and was, for a time, the anonymous legal expert on two programs on the ABC.

David Selby died on 16 September 2002. He was survived by his wife of 63 years, the former Barbara Phillips and a son and two daughters. He was a member of NAJEX for many years.

His obituary by Jen Rosenberg was published in the Sydney Morning Herald on 3 October 2002.

His Obituary by his grand daughter, Jane Albert, was published in The Australian

Written by David Selby’s daughter, Alison Rosenberg.